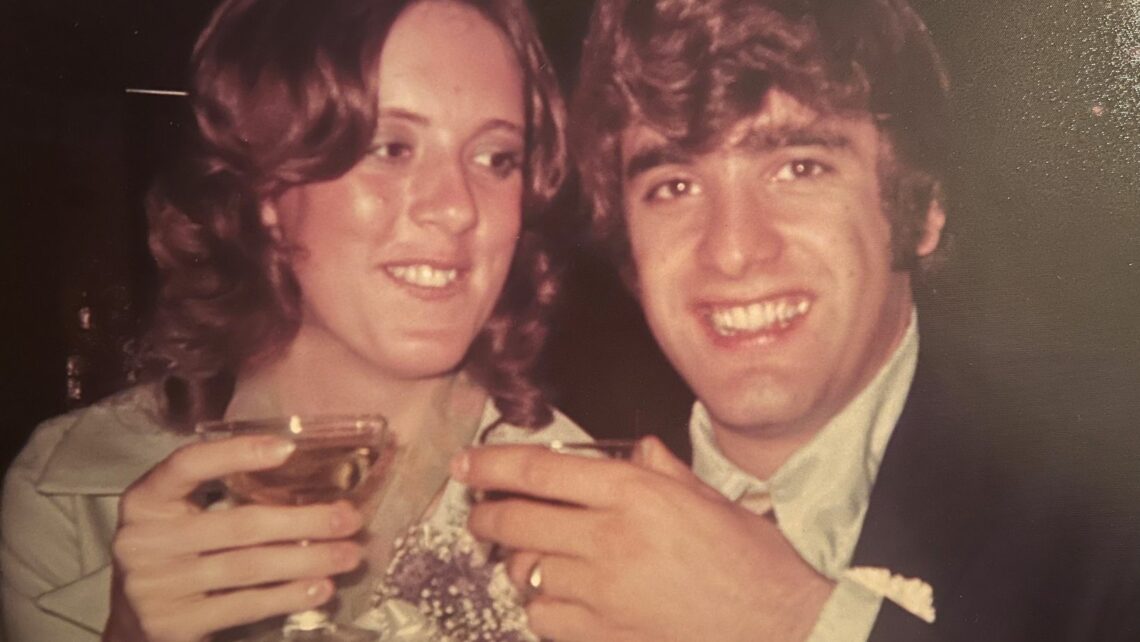

Look at this photo and you likely see a glamorous young couple leaning hard into the fashion of the early 1970s. I look and see my pretty, young mother and my handsome, young dad. But there’s someone else there, too. I’m in this photo. These two people knew I was there, but neither of them knew who I was…yet. In fact, it’s not an overstatement to say that I am the reason for this photo.

June 24, 2022: I, along with many in the country, am reeling at the ruling handed down by the Supreme Court this morning. For nearly the entirety of my existence, Roe v. Wade has been in place. January 22, 1973, a mere 24 days after my birth, the Supreme Court found that “the Constitution of the United States generally protects a pregnant woman’s liberty to choose to have an abortion.”

This photo was taken a little more than six months before this ruling was announced, but access to an abortion is how this photo came to be taken.

This isn’t a post about choosing life, despite the fact I am here and I am a mother because that decision was twice made. This also isn’t a post about the pro-choice side; I have private feelings about abortion, but I intend to fight this decision in as many ways as I can to ensure that every woman has the right to make that decision for herself. If the Supreme Court can change its mind once, then it can change it again.

Rather, this is a post about a warm day in June of 1972 and how I’m attempting to work through it all these many years later.

My conception was in March 1972, 10 months before Roe v. Wade became a household phrase. 19-year old Bonnie Bowman and 22-year old John Del Val hadn’t been dating for very long when they discovered they were expecting a baby. He was a senior from New York state; she was a freshman from the southwest corner of North Dakota. I don’t know this for certain, but I don’t think either of them thought this relationship would be permanent. I think it was fun and they liked each other fine enough.

They realized she was pregnant in May. They considered their options. My dad called the hospital where he’d been born in Port Chester, NY, and found out they performed abortions; it was one of the few places across the country that could legally do them in 1972. At least they knew they had a choice. My dad graduated from Jamestown College and went back to Rye, NY, for a summer job. My mom went back to Bowman.

When they learned of it, my maternal grandparents felt that abortion was my mom’s best choice. They put her on a plane, three months pregnant, and she flew across the country to terminate this very real problem. I say that from a place of certain knowledge and with no judgment. Believe me, when I was considering terminating my own “problem” 23 years later, I wasn’t thinking about a perfect baby who would turn into a quirky little boy who would become a stellar young man. I was simply frantically trying to erase the enormous mistake I had made and get back to the path I was supposed to take.

My mom says that when they drove past the hospital the day she arrived in New York, she looked at it and said to my dad, “I can’t have an abortion.”

She doesn’t remember what he said, but she does remember that he was kind and supportive. My paternal grandparents were virtually as unhelpful as the other set. Nobody quite knew what to do. She remembers that she and my dad felt utterly adrift and without any real support.

In the absence of the abortion, the “problem” was clearly still present. So my parents did what couples did in 1972. They first went to the Catholic church where my Italian American dad had been raised. Upon hearing that she would have to agree to raise this baby Catholic, my young mother said, “No, thank you.”

Then they went down the street to the Methodist church where a kind minister agreed to marry them, no strings attached.

On June 28, 1972, six months and one day before I arrived on the scene in any real sense of the word, my mom put on the best dress she had packed for the quick trip East. It was pale green and so, so short. We had that dress for years in a cedar chest until the synthetic lining literally disintegrated, and she put it in the garbage. I feel like that dress and their marriage left my life around the same time.

There were very few people at their wedding. My dad’s two good friends and their wives, the minister, and the three of us.

They went out to eat afterwards—hence this photo, the only one taken the day of their wedding. By the way, this is also the only photo ever taken of either of my parents holding alcohol. I’d bet my house that my mother drank none of her Champaign and my dad drank very little of his. When I say, as I so often do, that I grew up around absolutely no alcohol, I’m not kidding.

I’ve been thinking so much about this anniversary coming up next week. Thinking about what it means to have 50 years pass. Thinking about the fact that I have always been the tip of the triangle that became John and Bonnie Del Val on June 28, 1972.

I have, at times, wondered if my dad resented that because of me, or because my mother chose not to terminate me, he ended up in North Dakota for his entire life. He certainly never expressed it to me if he did. Many of my fondest memories of being a little girl involve my dad—having tea parties, playing board games, watching Wimbledon on tiny, grainy televisions together.

What would the world be like if not only I but my two brothers, my son and my two nieces and one nephew didn’t exist? It’s not as if any of us has been such an extraordinary part of humanity or made a life-saving contribution to the world, but we have played our parts, and who knows who or what is yet to come?

When I was frantically trying to decide what to do with my own unplanned pregnancy, I called my stepdad, the wisest spiritual man I knew. I asked him if I would go to hell if I had an abortion.

He paused for a minute, the silence on the phone deafening to my ear. He said, “D, I won’t even begin to speculate on that. There’s someone without a voice that needs representation. You are the only voice for this little soul; only you can speak for it. Every person is a thread in the fabric of humanity, and when you cut one out, when you pull it from the fabric, it weakens the whole and eventually leaves a hole. But you need to do what you need to do.”

I had incredible guidance, love and support when I found myself in a hard spot. Both my biological parents stepped up in beautiful ways, perhaps because they easily recalled their own parents’ failures when they were in the same boat. My stepparents reached out. My ex-boyfriend’s parents were incredible. My best friend and my roommate that summer picked up so many pieces. And there were others who carried some of this burden when I simply couldn’t do it. I was never truly alone. Who did my parents have? Who counseled them? Who answered their existential fears with an answer that still allowed for them to make decisions? Who guided their choices?

I look at these two very young people in this photo, and I see the hope that they are doing the right thing in their eyes. I see that they understand they are now inextricably tied together for the rest of their lives. I see happiness and fear; confidence and terror; hope and hesitancy.

I can’t quite work out my complicated emotional state today. I appreciate that my mother didn’t have an abortion, although I wouldn’t know it if she had, of course. I am grateful beyond measure that I also turned that option down, but I believe with all my heart that having the choice is the greatest point.

Some could argue that keeping that baby in 1972 derailed two young people who would have gone on to have completely different lives. What didn’t happen in the world because they forged their path together? Maybe all my angst and melancholy comes from having been conceived and formed in such emotional turmoil and upheaval.

But my parents got to make their choice. Nobody forced a single piece of this story on them. They made decisions at every turn, and they’ve paid the price for and garnered the fruits of those decisions ever since. And I have, too.

My mother and I both chose motherhood, but the important word in the sentence is “chose.” In my mother’s case, she added marriage to the mix; in mine, I did not. I’ve often speculated that had my parents’ marriage worked, I imagine I, too, would have gotten married. To be fair to Quinn’s dad, he would absolutely have married me if I had wanted that. But I was fewer than 10 years from my parents’ divorce when I found myself pregnant, and I knew I wanted to avoid that if at all possible. My parents were spectacularly supportive of my decision to not get married. Quinn’s dad stayed in the picture, and they’ve forged their own relationship.

I’ve taken for granted my entire life that the right to choose how and when I would become a mother, if at all, was just that…a right. In fact, I’ve hardly considered it anymore than I’ve spent time considering the fact that I got to go to college, get my own credit card, purchase my house without my father or husband’s permission.

The spring of 1972 was a tumultuous time in the lives of Bonnie Bowman and John Del Val as well as for the Supreme Court and the nation. Each was wrestling with what direction to take this weighty issue. My parents’ wedding, my birth and the passing of Roe v. Wade are forever braided together. And now the 50th anniversary of their marriage, the dismantling of Roe v. Wade and my upcoming 50th birthday are, too.

I don’t know how to reconcile any of this. I look out at the landscape and see happiness and fear; confidence and terror; hope and hesitancy. And I wonder, what will it all be like on June 28, 2072?